Human intelligence evolved through the utility of our hands as we learned to wield tools and shape our environment. For robots to advance, they must learn this same language of dexterity.

As we continue to develop physical AI that can both understand and navigate the physical world, a key piece will be teaching intelligent robots how to use tools to interact with the world around them. In robotics, this capability is known as ‘fine manipulation.’

What is fine manipulation?

Fine manipulation refers to a robot’s ability to interact with the world through objects. This skill takes more than just motor control – it requires the robot to be capable of perceiving, understanding and acting within a situation in real time.

While to us this is a simple skill learned in infancy, AI-driven robots must learn this skill from scratch. To them, state space is massive. Even a simple instruction, such as rearranging a cluttered factory floor, can correspond to countless possible world states. To complete our instructions safely and efficiently, they require a clear understanding of the environment and the ability to plan their actions, whether the task is as big as moving heavy equipment or as seemingly small as handing a cup to a person without spilling it. Without this essential skill, physical AI will fall short of its immense potential.

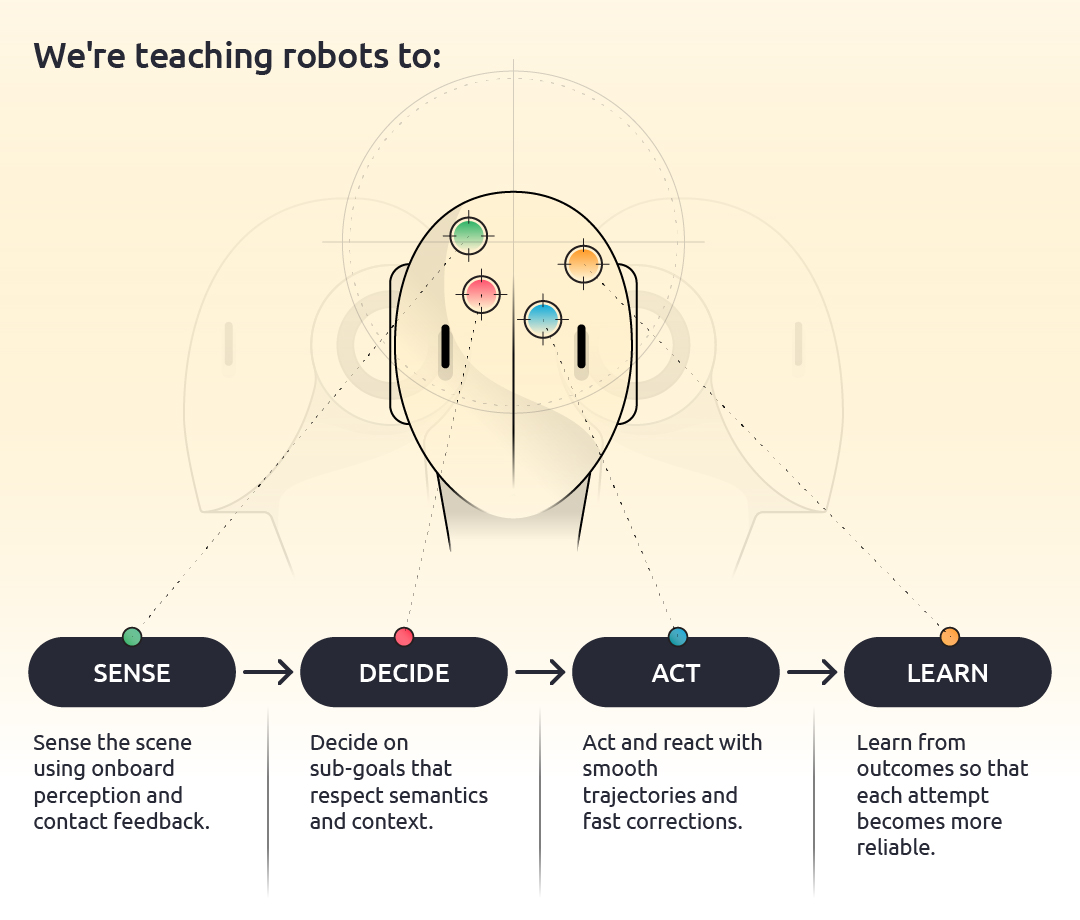

For robots, as with humans, this essentially boils down into a single feedback loop: Sense → decide → act → learn. We’re teaching robots to:

- Sense the scene using onboard perception and contact feedback.

- Decide on sub-goals that respect semantics and context.

- Act and react with smooth trajectories and fast corrections.

- Learn from outcomes so that each attempt becomes more reliable.

As these steps reinforce one another, emergent capabilities appear: a stronger grounding of language in perception, more reliable grasp of different objects, and better recovery and learning from demonstration data rather than explicit planning.

Although fine manipulation can be used across different forms of robotics, humanoid robots will play a special role as their bodies are already aligned with the way the world is built. Dual arms and dexterous fingers can handle tools and objects designed for human hands; a torso and waist give extra reach and allow them to bend down, work in tight spaces and naturally approach shelves, tables and machines. This human-like embodiment built with fine manipulation and whole body control makes it easier to reuse existing environments, workflows and tools, allowing smoother commercialisation and deployment into the real world.

Our approach to fine manipulation

To ready physical AI for real-world use and realising its full commercial potential, developing reliable and repeatable fine manipulation systems in intelligent robotics will be nothing short of essential.

To achieve this goal and achieve this vital dexterity, we’re layering the strengths of several different approaches: the precision of classic robotics, the perception and generalisation of foundation AI models and the adaptability of human-like feedback loops. By leveraging state-of-the-art foundation models where they add the most value and combining them with proven traditional control methods, we’re on our way to creating safe, reliable and adaptable fine manipulation system that can run across different platforms.

Classic robotics methods rely on geometric models and rule-based planning. Modern embodied AI extends these capabilities by teaching how perception, reasoning and control can combine with language, vision and multimodal data. We combine these approaches to achieve both stability and learned adaptability.

To handle complex, long-horizon manipulation, we use an architected control system combing classic and learned models that knows when to rely on learned models and where to apply deterministic control. The system combines the generalisation of modern world models, the interpretability of AI/RL modules and the robustness of classical controllers.

Consider a pick-and-place task: moving an object from a collection point to a cupboard and placing it on the correct shelf. A conventional pipeline detects edges, reconstructs 3D geometry, plans a grasp and generates precise joint trajectories, but this often breaks down when faced with clutter, occlusion or poor lighting, where grasp localisation becomes unreliable.

To improve this stage, a foundation vision model can be trained on tele-operated box-lifting demonstrations. It infers object pose and grasp points directly from images, improving grasp reliability and allowing recovery from partial failures. Once the object is secured, control can switch to classical trajectory and joint-space control for transport.

Navigation to the cupboard can be handled by an RL or planning module that manages paths and obstacles, and when the robot reaches the cupboard a vision system can identify the right cupboard and candidate shelves. The choice of which shelf to use (e.g. top vs bottom) can come from a simple decision tree or a higher-level vision language action model (VLA) that reasons over the goal and scene, with the final placement again carried out by the lower-level VLA and controller.

In the video above, we show the grasping and shelf-selection parts of this pipeline running on a humanoid. In the tabletop scenes, the robot uses a VLA policy to decide whether to grasp, what to grasp and where to place its hands on the box while controlling the initial lift until the box is stable. From that point, a classical controller moves the box around and places it back on the table, letting the VLA focus on the harder parts: recognising the object, handling different colours and orientations, ignoring non-target items and recovering from slips.

In the shelf scenes, the VLA runs end-to-end: the hands move through a narrow gap and pull the box out cleanly, which tests whether the policy is really reasoning about geometry and contact. We use the same model for both top and bottom shelves; only the language prompt changes (“pick from the top shelf” vs “pick from the bottom shelf”), showing how the behaviour can be steered by instruction without swapping models and hinting at how this stack can be connected to higher-level planners for longer-horizon tasks.

Taken together, this example and demo show how the system blends a world model for perception and grasp inference, AI modules for decision-making and classical controllers for precise, safe execution.

This is how real systems are built. Many of the demo videos we see online hide these layers and what’s happening behind the scenes, but we believe true reliability comes from how the learned and classical components are stitched together and balanced at each stage. This is exactly why we’ve chosen to show each step of our journey into physical AI development, pulling back the curtain on the complex work needed to take physical AI from deep tech to real-world impact.

Challenges and progress in perfecting fine manipulation

Following this approach, our team has quickly progressed from a lab proof-of-concept to stable pick-and-place cycles within real hardware. We’ve developed an in-house data collection strategy that is customisable to the robot embodiment and targeting skill. Our data pipeline now runs five times faster than the academic norm, and a single skill can be fine-tuned from scratch with roughly 15 minutes of high-quality tele-op video.

Gathering high-quality data at this speed addresses a key bottleneck for companies planning to use foundation models, bringing us closer to real-world impact. So far, this has allowed the model to learn faster and with less data while remaining robust against lighting, background and clutter, leading to a near-100% success rate for first attempts when trying to pick up a box and automatic reattempts if grasp slips.

Part of the challenge is that many of these systems behave like a ‘black box’: their complexity makes failures hard to interpret, safety difficult to certify and behaviour in new situations hard to predict. To address this challenge, we’re looking at how AI behaves in real scenarios, not just simulation, to help us better predict behaviour and ensure it still meets operational and safety requirements, even when the environment changes.

Our data strategy and take-specific design allows us to observe the gap between how to system behaved when the data was collected and how it behaves now so we can better understand where it is likely to fail. By controlling and limiting the information that flows into the model as well as monitoring its state when the robot performs and action, we can ensure its behaviour remains safe while still allowing the AI to learn and adapt. Through this strategy we can pinpoint what went wrong, correct it, and keep the overall system both explainable and safe enough for real-world use.

The first industries that will benefit from this progress are organisations that need quick, task-specific autonomy without months of data collection, such as e-commerce and logistics companies, manufacturing, hospital supply and sterile labs or hazardous environment navigation.

But the humanoid-specific data we need to continue to train the programme remains scarce. High-quality physical data is expensive, slow to collect and often specific to a single robot. Large, diverse datasets are needed for multi-skill manipulation and even fine-tuning foundation models typically demands tens of thousands of examples for a new embodiment. Synthetic data helps pretraining, but real data is still required to close the reality gap.

This is the price of working at the cutting-edge – we’re building new capabilities almost from scratch. Even so, we’re seeing exciting progress. With a combination of capabilities in fine manipulation, human-robot interaction, whole body control and sim2real data, we’re moving ever closer to a step-change for robotics with a new class of physical AI.

Follow along with our progress and reach out to continue the conversation on how physical AI can move beyond the lab and into the real world.